In 1993, I was a student at the State University of New York-Albany when Dr. Marta Moreno Vega came to speak on our campus. Until that evening, I had never heard the term Afro-Latina. In fact, I had just learned what it meant when someone said “African descendant.” See, even though I had grown up in NYC and Westchester County, respectively, and completely embraced and understood that I was Puerto Rican, it was not until I went to college that I began to get to know who I TRULY was.

The year before, I had joined the Albany State University Black Alliance and, through my involvement with peers who were racially and politically conscious, I was exposed to the true history of mi gente (my people). This awakening of my racial consciousness would lead me to become an Africana Studies major and, to this day, I have been a scholar-activist in the field of Black studies. For me, it became clear that I was an African descendant, so I began to devour anything and everything I could, not only to learn the truth of who I was but also to confront the lies I had been told by my teachers, family and TV.

Although I began to identify as an African descendant, it was not until I joined the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement in 2000 that I began to identify as Black, and identifying as such was not easy for me. In too many movement spaces, conscious gatherings and panels, I far too often was confronted and accused of selling out as a Latina. Without the mentorship of Marta and the late Richie Perez, as well as my comrades in the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement and others, I could not have navigated “conscious” movement and personal spaces that sought to take away my Blackness. I have identified myself as a Black Puerto Rican woman since 2001 and to this day, it is not easy. Although many Latinx* people, especially younger ones, are now identifying as Afro-Latinx, I often wonder if it is easier to embrace cultural identifications as opposed to embracing Blackness not only as phenotype but also as a political signifier.

I cannot tell you how many times in the past few years I have been asked, “Why are you here? You are not Black.” “Why are you here? You are a non-Black person of color.” What many movement people, leaders, foot soldiers and woke folks fail to understand is that, in America, the binary of Black and white has always excluded “Latinx” people. One need only look at the media to see that, even in 2017, Blackness in America means African-American. Never are we as Black Latinx people represented in the media, and you will rarely find Africans and Black Caribbean people in dialogues and discussions about race.

Despite the growing numbers and growing racial consciousness of Afro-Latinx people, much of the prevailing discourse makes the assumption that we either have to subscribe to the dominant racial paradigm of African-American/white-American discourse or have to choose between our Black identity or our ethnic one. Going back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Pan-Africanism signaled for the first time an explicit, organized identification with Africa and African descendants and, more expansively, of nonwhite peoples at a global level. With the United States’ occupation of Cuba and Puerto Rico and the ever-growing migratory presence of both populations in New York and other northeastern cities, the central cultural concern of Afro-Latinx became their relationship with African-Americans and, more globally, with an African diasporic world. This Pan-Africanist ideology was embodied most prominently by Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, a Black Puerto Rican who took part in anti-Spanish liberation struggles. Schomburg, a collector and bibliophile of worldwide Africana experiences, contributed greatly to the burgeoning field of Black history. Schomburg lived his life on the color line. His direct knowledge and experience of racism, both in Latin America and the United States, and his alliances with other prominent African-American historians at the time was groundbreaking, and, at the end of his life, Arturo Alfonso Schomburg would identify himself as a Black man.

As Black History Month ends, it is incumbent that we as Afro-Latinx people in the United States heed the work of Frantz Fanon, who wrote extensively about decolonizing the mind. It also is necessary that movement organizers, organizations and those that fight for social justice affirm and acknowledge a new generation of unapologetic Afro-Latinx, Black Latinx young people who are taking their rightful place in the Black radical tradition. As one of my favorite groups, the Welfare Poets, said on their album Project Blues:

“Who we be? Who I be? Who we be? We be I…singular I, now the essence of los Africanos and that of lo Indio run within me. So, when you call me Spanish, all my purity seems to vanish because that is not who I be. So, don’t refer to me with words that blur the trueness to my identity, defining me by a colonizer’s language, disregarding my family lineage, my ancestral heritage. Now, I be the rhythm of the Congo, played to an internal bomba, extending from Nigeria from a culture called Yoruba.”

No one will ever stop my Blackness. It is who I be.

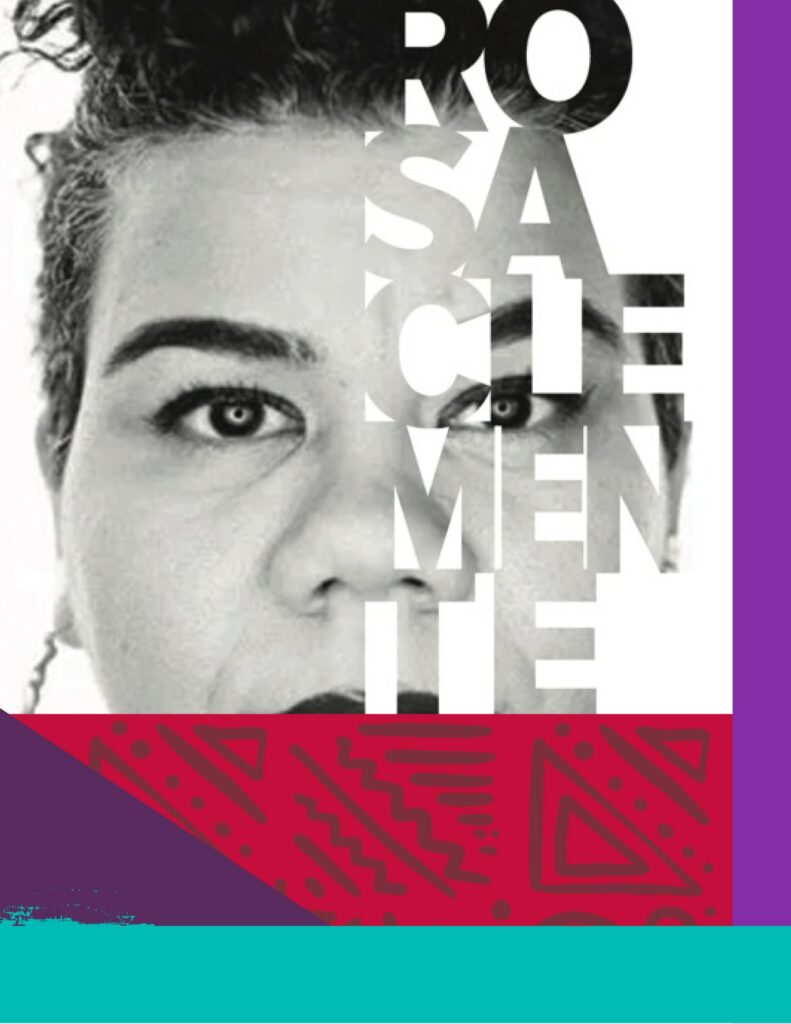

Rosa Alicia Clemente is a doctoral candidate at the W.E.B. DuBois Department of Afro-American Studies at UMass-Amherst and was the 2008 Green Party vice-presidential candidate. You can read her groundbreaking article Who is Black? and much more at www.rosaclemente.net.

*Latinx (pronounced “La-TEEN-ex”) is a gender-inclusive way of referring to people of Latin American and African descent. Used by activists and academics, the term is gaining traction among the general public. As Spanish is a gendered language, which means that every noun has a gender — in general, nouns that end in “a” tend to be feminine, and nouns that end in “o” tend to be masculine — people have been using the term more often to encompass nongender-conforming people.