Lee este artículo en español.

Yesterday, an interesting thing happened to me. I was told I am not Black.

The kicker for me was when my friend stated that the island of Puerto Rico was not a part of the African Diaspora. I wanted to go back to the old skool playground days and yell: “You said what about my momma?!” But after speaking to several friends, I found out that many Black Americans and Latinos agree with him. The miseducation of the Negro is still in effect!

I am so tired of having to prove to others that I am Black, that my peoples are from the Motherland, that Puerto Rico, along with Cuba, Panama and the Dominican Republic, are part of the African Diaspora. Do we forget that the slave ships dropped off our people all over the world, hence the word Diaspora?

The Atlantic slave trade brought Africans to Puerto Rico in the early 1500s. Some of the first slave rebellions took place on the island of Puerto Rico. Until 1846, Africanos on the island had to carry a libreta to move around the island, like the passbook system in apartheid South Africa. In Puerto Rico, you will find large communities of descendants of the Yoruba, Bambara, Wolof and Mandingo people. Puerto Rican culture is inherently African culture.

There are hundreds of books that will inform you, but I do not need to read book after book to legitimize this thesis. All I need to do is go to Puerto Rico and look all around me. Damn, all I really have to do is look in the mirror every day.

I am often asked what I am—usually by Blacks who are lighter than me and by Latinos/as who are darker than me. To answer the $64,000 question, I am a Black Boricua, Black Rican, Puertorique’a! Almost always I am questioned about why I choose to call myself Black over Latina, Spanish, Hispanic. Let me break it down.

I am not Spanish. Spanish is just another language I speak. I am not a Hispanic. My ancestors are not descendants of Spain, but descendants of Africa. I define my existence by race and land. (Borinken is the indigenous name of the island of Puerto Rico.)

Being Latino is not a cultural identity but rather a political one. Being Puerto Rican is not a racial identity, but rather a cultural and national one. Being Black is my racial identity. Why do I have to consistently explain this to those who are so-called conscious? Is it because they have a problem with their identity? Why is it so bad to assert who I am, for me to big-up my Africanness?

My Blackness is one of the greatest powers I have. We live in a society that devalues Blackness all the time. I will not be devalued as a human being, as a child of the Supreme Creator.

Although many of us in activist circles are enlightened, many of us have baggage that we must deal with. So many times I am asked why many Boricuas refuse to affirm their Blackness. I attribute this denial to the ever-rampant anti-Black sentiment in America and throughout the world, but I will not use this as an excuse. Often Puerto Ricans who assert our Blackness are not only outcast by Latinos who identify more with their Spanish Conqueror than their African ancestors, but we are also shunned by Black Americans who do not see us as Black.

Nelly Fuller, a great Black sociologist, stated:

[clickToTweet tweet=”Until one understands the system of White supremacy, anything and everything else will confuse you.” quote=”Until one understands the system of White supremacy, anything and everything else will confuse you.” theme=”style3″]

Divide and conquer still applies.

Listen people: Being Black is not just skin color, nor is it synonymous with Black Americans. To assert who I am is the most liberating and revolutionary thing I can ever do. Being a Black Puerto Rican encompasses me racially, ethically and most importantly, gives me a homeland to refer to.

So I have come to this conclusion: I am whatever I say I am! (Thank you, Rakim.)

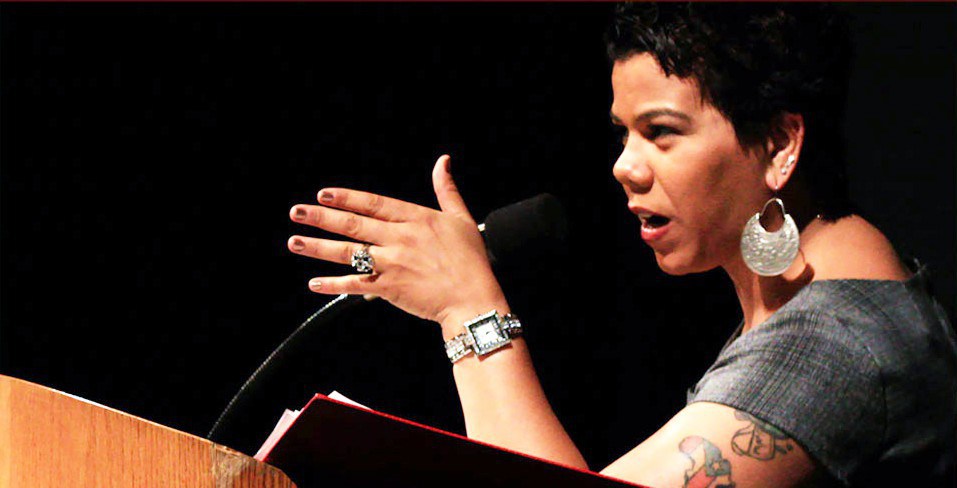

This article is written by Rosa Clemente and appeared first on Final Call.